MAHA, Ultra-Processed Foods, and Brain Addiction Claims

Summary

“Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) often spotlights ultra-processed foods as a major driver of poor health. This video adds a sharp twist: a top NIH researcher describes work testing whether high-fat, high-sugar ultra-processed foods change the brain’s dopamine response like addictive drugs, and says the data did not support the “as addictive as crack” narrative. The bigger concern raised is censorship, including blocked interviews and constrained publication and speaking. For everyday people, the practical takeaway is to focus on measurable eating habits and reliable information, not viral claims.

🎯 Key Takeaways

- ✓The video challenges the claim that ultra-processed foods trigger dopamine changes like highly addictive drugs.

- ✓A central concern is scientific censorship, including limits on publishing, speaking, and talking to journalists.

- ✓Public health messaging can backfire when it relies on dramatic addiction comparisons instead of careful evidence.

- ✓You can reduce ultra-processed foods without buying into oversimplified narratives, focus on patterns you can sustain.

- ✓If eating feels compulsive or distressing, support from a clinician can help, regardless of the political debate.

Ultra-processed foods are an easy target in public health conversations.

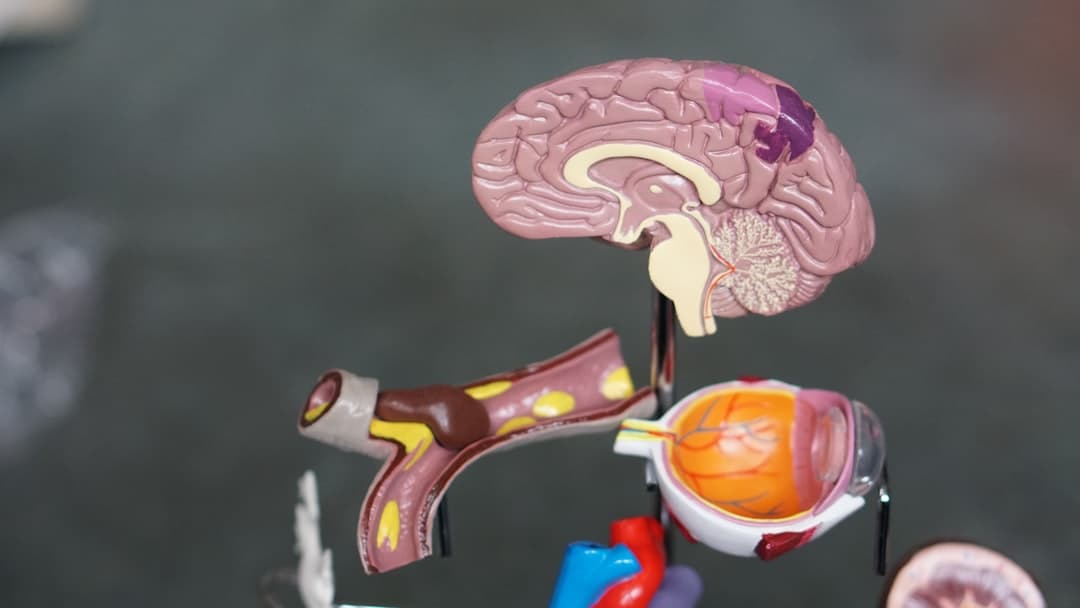

But the nervous system angle matters, because a lot of the loudest claims are really brain claims, things like “this food hijacks your dopamine like a drug.”

This video’s unique perspective is not “UPFs are harmless.” It is more no-nonsense than that: if a movement says it is fixing the problem, you should see relentless, transparent follow-through, not blocked communication and simplified narratives.

Why this MAHA debate matters for your nervous system

MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) is framed here as frequently targeting ultra-processed foods. The discussion pushes on a practical question: if leadership truly wants to solve the problem, are they actively engaging experts and communicating clearly?

The answer offered in the clip is blunt: “Um, no, not at all.”

That matters because the brain is often used as the persuasive hook. Dopamine, cravings, and “addiction” language can be motivating, but it can also distort what we know and do not know.

Did you know? Dopamine is a neurotransmitter involved in motivation and learning, not a simple “pleasure chemical.” Oversimplifying it can make health claims sound more certain than the science actually is. Learn more about dopamine basics from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and StrokeTrusted Source.

The video’s core claim: UPFs did not look like “crack” in the brain

A key moment centers on a piece of research the NIH health lead was excited about. The research question was specific: whether ultra-processed foods high in fat and sugar can cause the same kinds of changes in the brain’s dopamine response as highly addictive drugs.

The reported finding in the video is equally specific: they “didn’t seem to have the effect that many addictive drugs do.”

In other words, this framing argues that the popular narrative, “it’s as addictive as crack,” does not appear to be supported by that dopamine-response comparison.

What the research shows: Public discussion often uses the NOVA system to define ultra-processed foods. NOVA describes UPFs as industrial formulations with additives and minimal whole-food structure, and it is widely used in nutrition research, see the NOVA classification overviewTrusted Source.

What this means in real life

You can still decide to cut back on ultra-processed foods for metabolic, cardiovascular, or general nutrition reasons. But this view emphasizes being careful about turning a nutrition problem into a drug-addiction analogy, especially when brain data do not line up neatly.

Pro Tip: If “addictive” language makes you feel hopeless, switch to a simpler metric: aim for one additional minimally processed meal per day. Consistency beats intensity.

When science cannot speak, your health information gets worse

The video raises a different alarm: censorship and manipulated communication. A reporter requested an interview about the findings for The New York Times, and the interview was denied. The speaker also describes limits on giving talks and publishing “in the normal way,” plus concerns about how results are communicated to the public.

That is not just politics, it is a health literacy issue. When credible institutions cannot communicate clearly, people fill the gap with influencers, speculation, and fear-based claims.

Important: If you are making big diet changes because of alarming headlines, consider checking the original source or discussing it with a registered dietitian or clinician, especially if you have diabetes, an eating disorder history, or take medications that affect appetite.

Practical steps you can take today (no hype required)

You do not need a perfect definition of “addiction” to eat in a way that supports your brain and body.

Expert Q&A

Q: If ultra-processed foods are not “like crack,” why do I feel out of control around them?

A: Feeling out of control can come from many factors, including stress, sleep loss, restriction dieting, and highly rewarding food combinations, without requiring the same dopamine signature as addictive drugs. If this causes distress, a clinician or dietitian can help you build a plan that addresses triggers and supports steady eating.

Jordan Lee, RD (Registered Dietitian)

Key Takeaways

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are ultra-processed foods truly addictive like drugs?

- This video highlights research suggesting ultra-processed foods high in fat and sugar did not show the same dopamine-response effects as many addictive drugs. Even so, some people may still struggle with cravings for many reasons, so it can help to focus on practical eating patterns and seek support if distressing.

- What is one simple way to cut back on ultra-processed foods?

- Try a 7-day “swap, not ban” approach: replace one ultra-processed snack or meal per day with a minimally processed option you enjoy. Track how your hunger and cravings change, and adjust gradually.

Get Evidence-Based Health Tips

Join readers getting weekly insights on health, nutrition, and wellness. No spam, ever.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.