Peter Attia, LDL, and the Missing Endothelium Piece

Summary

A striking moment in this video is the presenter’s case of a 24-year-old endurance runner with extremely high LDL and ApoB, yet excellent metabolic markers, raising a real-world question: are numbers alone enough to judge risk? The video’s core message is nuanced. LDL and ApoB matter, but they are necessary and not sufficient to explain atherosclerosis. The “milieu” matters, especially endothelial health, blood pressure, insulin resistance, and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. The discussion emphasizes triglycerides and ApoB as high-yield markers, encourages adding lipoprotein(a) testing, and argues for looking beyond standard LDL-C to particle biology and context.

🎯 Key Takeaways

- ✓The video’s central framing is that LDL and ApoB are necessary for plaque risk, but they are not sufficient, endothelial injury and metabolic dysfunction shape whether particles become harmful.

- ✓Triglycerides are treated as an underappreciated risk signal, especially when they rise above roughly 100 mg/dL, because they can reflect insulin resistance and change lipoprotein composition.

- ✓CETP-driven lipid exchange can make triglyceride-rich particles more cholesterol-rich and longer-lived, while LDL and HDL can become more triglyceride-rich and cholesterol-poor, complicating interpretation of LDL-C and HDL-C.

- ✓A practical “poor man’s” screen discussed is the triglyceride-to-HDL ratio, with the video aiming for about 1:1 when metabolically healthy.

- ✓The metabolically healthy, very active person with high LDL-C and ApoB is presented as an unresolved clinical gray zone, where context, additional markers, and careful risk assessment matter.

- ✓The video strongly encourages testing lipoprotein(a) and considering ApoB alongside ApoA1, rather than relying on a standard lipid panel alone.

A 24-year-old runner with sky-high LDL, what do you do with that?

The video opens with a scenario that feels almost designed to stress-test modern cholesterol advice.

A 24-year-old man, running daily for years, cold plunging every morning, delaying his first meal until around 10:00 a.m., and showing what looks like exceptional fitness and low blood pressure. Then his labs come back with a total cholesterol of 416 mg/dL, LDL-C around 364 mg/dL, and ApoB around 220 mg/dL.

That single case becomes the lens for the entire episode’s unique perspective. Not because it proves anything by itself, but because it forces a practical question: when someone looks metabolically healthy, how confidently can you interpret very high LDL and ApoB as a direct forecast of future plaque?

This is where the video is deliberately nuanced. It does not argue that LDL is irrelevant. It also does not accept the idea that LDL alone fully explains risk.

Instead, the framing is almost environmental: cholesterol is like the “car on the road,” but the real determinants of crashes include the road conditions and driver behavior. In vascular terms, the “road conditions” are your endothelium, blood pressure, insulin resistance, smoking status, sleep apnea, oxidative stress, and overall metabolic health.

Important: If you ever see extreme lipid values (like LDL-C in the 300s or ApoB above 200 mg/dL), it is worth discussing promptly with a clinician. Very high levels can sometimes reflect inherited lipid disorders, and those deserve professional evaluation.

The specific lab context the video highlights

A subtle, practical point appears in the case description: the blood draw happened after the person did a cold plunge and a run, and it was fasted.

That matters because strenuous exercise can temporarily shift certain labs. For example, intense exercise can raise creatine kinase and sometimes changes lipid and triglyceride readings in ways that look alarming out of context.

This does not mean “ignore the numbers.” It means interpret them like a snapshot taken mid-movie.

The video’s core thesis: cholesterol is necessary, not sufficient

The discussion centers on cardiovascular disease being the leading cause of premature death for men and women, which is consistent with public health data from the World Health OrganizationTrusted Source.

Within that big picture, the video emphasizes a point often attributed to Dr. Peter Attia’s general stance: lower LDL-C and lower ApoB are usually considered better in many clinical frameworks.

Then comes the pivot.

The argument here is that cholesterol is necessary but insufficient to fully explain atherosclerosis. In other words, ApoB-containing particles (LDL, VLDL remnants, lipoprotein(a)) may be required ingredients, but plaque formation depends heavily on whether the vessel wall is vulnerable.

This is not a minor distinction. It changes what you do day-to-day.

If you treat LDL as the whole story, your plan becomes almost entirely about lowering LDL. If you treat LDL as one required ingredient in a broader process, you also prioritize protecting the vessel wall and improving the metabolic environment that influences how particles behave.

Atherosclerosis is widely understood as a chronic inflammatory process involving retention of ApoB-containing lipoproteins in the arterial wall and subsequent immune activity. This general concept aligns with major scientific statements, including the European consensus that emphasizes ApoB lipoproteins as causal in atherosclerosis, while also acknowledging broader biology and risk context, see European Atherosclerosis Society consensusTrusted Source.

But the video’s unique emphasis is not simply “ApoB causes disease.” It is “ApoB matters, and the endothelium decides how dangerous the exposure becomes.”

Why triglycerides became the surprise hero of the conversation

A standout moment in the video is the presenter’s surprise that Tom Dayspring, a lipid-focused clinician, elevates triglycerides to near co-equal status with ApoB.

The clip highlighted is blunt: if limited to only two biomarkers, the choice would be triglycerides and ApoB.

That is a very specific viewpoint, and it drives much of the practical advice that follows.

Triglycerides are framed as more than “another number on your lipid panel.” They are treated as a window into insulin resistance and into the presence of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (like VLDL and remnants) that can be highly atherogenic.

One of the most actionable claims in the video is that risk signals may start earlier than many people assume. Instead of waiting until triglycerides are above 150 mg/dL, the presenter argues that shifts in lipoprotein cargo and risk may begin when triglycerides are around 100 mg/dL or higher.

That is not a universal clinical cutoff, but it is the video’s practical threshold for paying attention.

Did you know? Many guidelines define “normal” triglycerides as below 150 mg/dL, but triglycerides can still reflect metabolic strain at lower levels in some people, especially when paired with low HDL. For reference ranges and interpretation, see the CDC’s triglycerides overviewTrusted Source.

The “poor man’s” ratio the video keeps coming back to

Instead of expecting everyone to get advanced particle testing immediately, the video suggests a simple screen:

This ratio is presented as a practical proxy for metabolic health and lipoprotein behavior.

Pro Tip: If you are tracking triglycerides, try to keep the testing conditions consistent, similar fasting duration, similar exercise timing, similar alcohol intake in the prior day or two. Small behavior differences can change the result.

CETP, “particle mating,” and why LDL-C can mislead

The most technical and most distinctive section of the video is the discussion of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) and how it changes lipoprotein cargo when triglyceride-rich particles are abundant.

The metaphor used is memorable: lipoproteins “mate.”

In plain language, the idea is this:

When triglyceride-rich VLDL particles are floating around, they interact with the more numerous LDL and HDL particles. CETP facilitates an exchange, swapping triglycerides and cholesterol between particles.

The video emphasizes two downstream effects:

This is one reason the video argues that LDL-C alone can be misleading, especially in insulin resistance.

It also explains a pattern many people have seen on basic labs: as triglycerides rise, HDL often falls, and LDL-C does not always rise in parallel.

This concept is consistent with broader lipidology discussions of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and remnant cholesterol as risk factors. For a mainstream overview of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and cardiovascular risk, see information from the American Heart AssociationTrusted Source.

Why ApoB is treated as a “count,” not just a cholesterol amount

ApoB is presented as valuable because it approximates the number of atherogenic particles circulating (each atherogenic particle carries one ApoB molecule).

LDL-C is more like the amount of cholesterol carried inside those particles.

If the cargo per particle changes, LDL-C can change without the particle count changing much, and vice versa.

That is the practical reason the video repeatedly returns to ApoB.

The “milieu” matters: endothelial health as the deciding factor

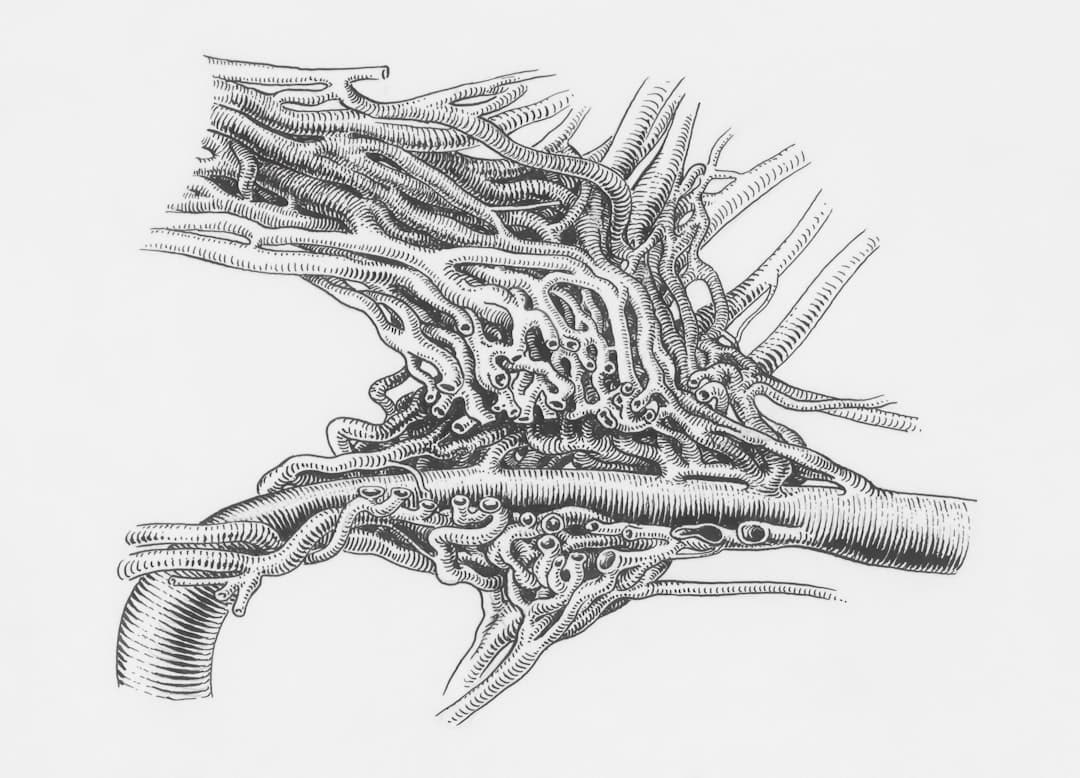

The video introduces a concept that is easy to remember: leaky vessels.

Just like people talk about “leaky gut” (intestinal permeability), the vascular system has a single-cell lining called the endothelium that can become damaged and dysfunctional. When that lining is unhealthy, the probability increases that lipoproteins can enter the arterial wall, become retained, and contribute to plaque.

This section is where the video’s perspective is most distinct from generic cholesterol content.

Rather than treating plaque as a simple story of “high LDL equals plaque,” the argument is that the endothelium is injured by specific stressors, including:

Then, in that injured environment, ApoB particles are more likely to become a problem.

One especially important detail is the claim that there is constant “flux” of cholesterol in and out of the vessel wall, and that a large portion of lipoproteins that enter the wall also leave without causing harm. The risk rises when particles become retained and provoke immune activity.

This aligns with the broader scientific understanding that atherosclerosis involves retention of ApoB-containing lipoproteins and inflammatory response, see NIH overview of atherosclerosisTrusted Source.

What the research shows: High blood pressure is a major, independent cardiovascular risk factor, and lowering blood pressure reduces cardiovascular events in many populations. For a guideline-based overview, see the American Heart Association’s blood pressure resourcesTrusted Source.

A practical lab strategy that matches the video’s viewpoint

The video’s lab philosophy is not “get every test imaginable.” It is “get the tests that clarify the story.”

A standard lipid panel can be a starting point, but it may not capture particle number, remnant risk, or inherited risk.

Here is a practical, video-aligned approach you can discuss with your clinician.

1) Start with basics, but interpret them as a pattern

Short and simple.

Patterns matter more than any single number.

2) Add ApoB to estimate atherogenic particle burden

ApoB is presented as a high-yield marker that many mainstream clinicians still do not routinely order.

This is consistent with major organizations that increasingly recognize ApoB as useful, particularly when triglycerides are elevated or when metabolic risk is present. For a clinical perspective, see the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology lipid guidanceTrusted Source.

3) Add lipoprotein(a) at least once

The video strongly encourages testing lipoprotein(a) (also written Lp(a)), describing it as an LDL-like particle with an attached protein (apo(a)).

Lp(a) is framed as particularly atherogenic, and the video mentions aiming for an Lp(a) less than about 10 mg/dL.

Different labs report Lp(a) in different units (mg/dL vs nmol/L), and “ideal” targets can vary by guideline and unit. Still, the practical takeaway is clear: Lp(a) is often genetic, and you usually need to measure it to know it is there.

For a patient-friendly overview, see the Cleveland Clinic’s Lp(a) explainerTrusted Source.

4) Consider ApoA1 and the ApoB:ApoA1 ratio

The video suggests looking at ApoB in the context of ApoA1, which is associated with HDL particles and reverse cholesterol transport.

The ratio is presented as one way to balance “delivery and deposition” risk (ApoB) against “removal and transport” capacity (ApoA1).

5) Consider advanced lipoprotein testing when triglycerides are high or the story is confusing

The video name-checks advanced particle testing options (examples include NMR-based methods and other commercial platforms).

The reason is practical: if LDL and HDL particles are becoming triglyceride-enriched and cholesterol-poor, LDL-C alone may underrepresent particle-related risk.

»MORE: If you keep getting mixed signals from standard labs (for example, low LDL-C but high triglycerides and low HDL), ask your clinician whether ApoB, non-HDL cholesterol, or advanced lipoprotein testing could clarify your risk profile.

The metabolically healthy high-LDL phenotype, what is known and unknown

This is the tension point of the entire video.

On one side is the well-supported idea that ApoB-containing particles are causal in atherosclerosis. On the other side is a real-world phenomenon: some people, often lean, active, and eating lower-carb diets, show very high LDL-C and sometimes high ApoB while maintaining low fasting insulin and otherwise strong metabolic markers.

The video’s stance is not to declare victory for either camp.

Instead, it emphasizes uncertainty and the need for better answers.

Why exercise can complicate interpretation

Another practical observation is that intense exercise can make certain labs look temporarily worse. The presenter notes cases where labs called patients because values suggested acute risk, even though the person had simply exercised hard.

This does not mean exercise is harmful.

It means timing and context matter.

Regular physical activity is consistently associated with lower cardiovascular risk in large bodies of evidence. For general guidance, see the WHO physical activity recommendationsTrusted Source.

The medication question the video raises, without answering it

The video explicitly asks whether a young, highly fit person with very high LDL-C should be placed on lipid-lowering medication, and what the long-term tradeoffs might be, including potential effects on performance.

No definitive recommendation is given.

That restraint is part of the video’s unique perspective. It highlights that population-level evidence does not always map neatly onto outlier phenotypes, and that risk assessment should be individualized with a clinician.

Expert Q&A

Q: If my LDL-C is high but my triglycerides are low, am I “safe”?

A: Not necessarily. The video’s framing is that LDL and ApoB still matter, but the overall environment matters too, including blood pressure, insulin resistance, smoking, and sleep apnea. Low triglycerides can be a reassuring sign of metabolic health, yet very high LDL-C or ApoB may still warrant deeper evaluation with ApoB, Lp(a), family history, and possibly imaging.

A clinician can help you interpret whether your pattern resembles an inherited condition, a diet-related shift, or a transient change from training and testing timing.

Health writer summary of the video’s approach, medically cautious, not a diagnosis

Everyday actions the video prioritizes (beyond “lower LDL”)

The most practical part of the video is the shift from “lipid obsession” to “endothelium protection.”

That means focusing on the mediators that injure vessels and make ApoB particles more dangerous.

A simple checklist of “endothelium stressors” to address

Short paragraph.

This is the “driver behavior” part of the car crash analogy.

How to use the triglyceride-to-HDL ratio in everyday life

This section is not about chasing perfection. It is about using a simple pattern to guide habits.

Recheck under consistent conditions. If your triglycerides were taken after a hard workout or unusual fasting, consider repeating under more typical conditions, after discussing with your clinician.

Treat rising triglycerides as a metabolic signal. The video’s practical threshold is that risk may start to increase when triglycerides are above about 100 mg/dL, especially if HDL is low.

Use the ratio to guide lifestyle focus. If triglycerides climb and HDL falls, that pattern can be a prompt to look at sleep, alcohol, ultra-processed carbs, weight changes, and training recovery.

Sauna, heat exposure, and the “exercise for the endothelium” idea

The video includes a sponsor segment, but it also reveals an underlying belief: heat stress from sauna may act like a form of vascular exercise by increasing blood flow and challenging thermoregulation.

Research on sauna bathing suggests associations with cardiovascular outcomes in observational studies, though this does not prove causation and may reflect overall lifestyle patterns. For a widely cited example, see a summary of Finnish sauna research in Mayo Clinic ProceedingsTrusted Source.

If you use sauna or heat exposure, basic safety matters, hydration, avoiding alcohol, and extra caution if you have heart disease or are pregnant. A clinician can advise what is appropriate for you.

Important: Heat exposure can lower blood pressure temporarily and can be risky for people prone to fainting, dehydration, or certain cardiac conditions. If you feel lightheaded, stop and cool down, and consider medical advice.

A practical “do this next” plan (video-aligned)

Expert Q&A

Q: What are practical signs of endothelial dysfunction the video mentions?

A: The video points to high blood pressure and sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction in men, and arousal-related blood flow issues in women) as possible clues, because they can reflect impaired blood vessel function. It also mentions exercise intolerance as a warning sign, for example being unable to do a small number of push-ups, as a rough signal of low fitness.

These signs can have many causes, so they are prompts for evaluation, not conclusions.

Health writer summary of the video’s approach, medically cautious, not a diagnosis

Key Takeaways

Frequently Asked Questions

- If I can only add one test beyond a standard lipid panel, what does the video suggest?

- The video strongly emphasizes ApoB as a practical next step because it reflects the burden of atherogenic particles. It also urges measuring lipoprotein(a) at least once, since it is often genetic and not visible on a standard panel.

- Why does the video treat triglycerides as more important than many doctors do?

- The video frames triglycerides as a proxy for insulin resistance and triglyceride-rich remnant particles that may be especially atherogenic. It also argues that rising triglycerides can change LDL and HDL particle cargo, making LDL-C and HDL-C less reliable by themselves.

- What triglyceride-to-HDL ratio does the video aim for?

- The video suggests aiming for about a 1:1 triglyceride-to-HDL ratio when metabolically healthy, using the example of triglycerides around 65 mg/dL and HDL around 65 mg/dL. This is presented as a practical screen, not a diagnosis.

- Can exercise make cholesterol labs look worse temporarily?

- Yes. The video notes that intense exercise, especially in a fasted state, can shift labs and even raise markers like creatine kinase, sometimes triggering alarm. If results are surprising, consider repeating labs under typical conditions with clinician guidance.

- What does the video mean by “leaky vessels”?

- It refers to endothelial dysfunction, where the single-cell lining of blood vessels becomes damaged or more permeable. In that environment, lipoproteins are more likely to enter and be retained in the arterial wall, increasing the chance of plaque formation.

Get Evidence-Based Health Tips

Join readers getting weekly insights on health, nutrition, and wellness. No spam, ever.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.