What “I Did My Own Research” Misses on Vaccines

Summary

Many people say “I did my own research” about vaccines, but often mean they read online opinions. The key point in this video is that real research is hard, time-consuming, and technical, often requiring immunology, virology, statistics, and epidemiology to interpret hundreds of papers. Instead of pretending we can replicate expert review overnight, a more practical approach is to understand how evidence is evaluated and why advisory committees exist. This article turns that perspective into everyday steps you can use to check claims, compare sources, and ask better questions at your next appointment.

What most people get wrong about “doing research”

“I did my own research” often means “I searched online and found people who agree with me.”

The video’s core critique is blunt: reading opinions about a vaccine is not the same as research. It can feel empowering to scroll, watch clips, and collect screenshots, but that process usually filters for emotion and familiarity, not accuracy.

This matters because vaccine decisions sit at the intersection of personal values and population-level evidence. When “research” becomes a synonym for “content,” it is easy to overrate a confident voice and underrate boring, technical data. A key insight from behavioral research is that overconfidence and distrust can travel together, especially when people feel excluded from expert systems, as described in a paper on the “I did my own research” phenomenon (overconfidence and (dis)trust in scienceTrusted Source).

Pro Tip: When you hear a claim, write it as a testable sentence (for example, “Vaccine X increases risk of Y”). If it cannot be tested, it cannot be “researched” in the scientific sense.

What “real research” looks like in vaccines

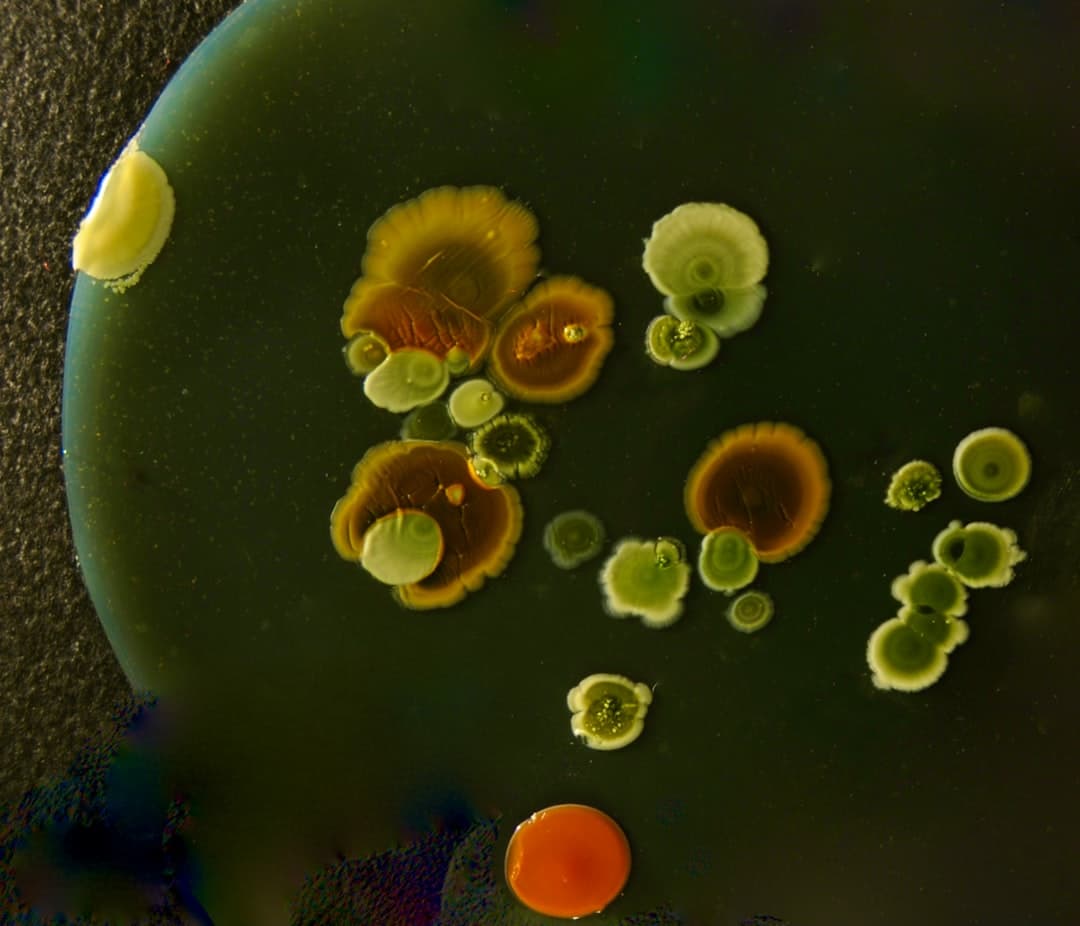

The speaker uses a concrete example: at one point there were roughly 300 papers published on the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine.

Reading those papers is only the beginning. This framing emphasizes the trade-off most people miss: you need time to read, plus the skills to interpret methods, statistics, bias, and clinical relevance. The video argues that doing this well typically requires expertise in immunology, virology, statistics, and epidemiology, and that few parents, and even few doctors, have deep mastery of all of those areas.

So what happens instead? The discussion highlights why advisory groups exist. Collectively, bodies like the FDA vaccine advisory committee and CDC vaccine advisory groups are designed to synthesize large evidence bases, including studies that disagree, and to update recommendations as new data arrives.

Did you know? The “DIY research” identity is often linked to confidence that outpaces actual evidence evaluation skills, a pattern explored in research on “I did my own research” rhetoric (full text hereTrusted Source).

Option A vs Option B: opinions-first vs evidence-first

Here is the practical comparison the video is pushing you toward.

Before vs After (mindset shift): Before, “research” equals searching. After, “research” equals checking sources, weighing quality, and noticing consensus.

Q: If even doctors may not know all the details, who can I trust?

A: Trust works better when it is specific. Instead of trusting a person blindly, trust a process: transparent evidence review, conflict-of-interest management, and updates when new data emerges.

Ask your clinician how they weigh evidence and what sources they rely on. If they can explain their reasoning and uncertainties clearly, that is a stronger signal than certainty alone.

Jordan Lee, MPH

How to vet a vaccine claim in 10 minutes

You do not need to read 300 papers to avoid being misled.

Important: If you have a history of severe allergic reactions, immune conditions, or prior vaccine reactions, do not rely on internet checklists alone. Discuss individualized risks and benefits with a qualified healthcare professional.

Key Takeaways

Sources & References

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is it bad to “do my own research” about vaccines?

- Wanting to understand is not bad. The key is matching the method to the question, prioritize primary sources and high-quality summaries over social media opinions, and ask a clinician to help interpret what applies to you.

- Why can’t I just read a few articles and decide?

- A few articles can be unrepresentative or low quality, especially if they are cherry-picked. The video’s point is that reliable conclusions often come from weighing many studies and understanding statistics, bias, and context.

- What should I ask my doctor if I’m unsure about a vaccine?

- Ask what the most common side effects are, what rare risks are known, what your personal risk factors are, and what evidence sources they use. Also ask what would change their recommendation, which tests how they handle new data.

Get Evidence-Based Health Tips

Join readers getting weekly insights on health, nutrition, and wellness. No spam, ever.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.