The Dangerous Cholesterol Lie and What Matters More

Summary

Most people were taught a simple story, cholesterol causes heart disease, so lowering cholesterol must prevent heart attacks. The expert in this video argues that this is the most dangerous cholesterol lie because it distracts from root causes like insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress. He also describes how cholesterol targets and guidelines shifted over time, and why that shift coincided with the rise of statins. Instead of focusing only on total cholesterol or LDL-C, he emphasizes LDL particle size, triglycerides to HDL ratio, hs-CRP, fasting insulin, A1C, and homocysteine as more meaningful markers to discuss with your clinician.

🎯 Key Takeaways

- ✓Cholesterol is essential, it supports hormones, vitamin D production, cell membranes, myelin, and bile acids.

- ✓The video’s central claim is that heart risk is driven more by insulin resistance, inflammation, and oxidative stress than by total cholesterol alone.

- ✓LDL quality matters, small dense LDL is framed as more concerning than large “fluffy” LDL, and standard LDL-C may miss that nuance.

- ✓Statins may lower measured LDL-C, but the presenter argues they do not directly fix the upstream drivers that damage LDL particles.

- ✓Practical lab discussions to consider include triglycerides to HDL ratio, hs-CRP, fasting insulin, A1C, and homocysteine, not just total cholesterol.

What most people get wrong about cholesterol

For decades, many of us have carried around a one-line health rule.

High cholesterol causes heart disease.

In the video, the presenter calls that rule the “number one most dangerous cholesterol lie,” not because cholesterol never matters, but because the story is too simple to guide real decisions. He argues that this oversimplification has shaped generations of fear, and it has helped normalize a medication-first mindset where people are told, “Take this pill, it will fix the problem.”

But “fix” is the word he pushes back on.

His central theme is that many medications, statins included, may change numbers on a lab report while leaving the underlying biology that created risk untouched. In his view, that can mask root causes and reduce the urgency people feel to change daily habits that drive metabolic health.

That is the unique perspective of this video, it is not primarily a cholesterol lecture. It is a story about how a single lab number became a cultural shortcut for cardiovascular risk, and how that shortcut may lead people away from better questions.

Those better questions, as he frames them, sound like this:

And if you are, what are you going to do about the drivers?

Important: If you take a statin or have been advised to start one, do not stop it based on a video or article. Use this information to have a more informed conversation with your clinician about your overall risk, your labs, and your options.

Cholesterol is not a toxin, it is a building material

The presenter spends a lot of time reframing cholesterol as normal, necessary, and deeply integrated into human physiology.

Cholesterol is not “foreign” to your body.

He emphasizes that your body manufactures most of the cholesterol it uses. From that starting point, he lists roles that are easy to forget when cholesterol is treated like a villain.

What cholesterol does in the body (as described in the video)

This section of the video is less about persuading you that cholesterol is “good,” and more about making it hard to call cholesterol inherently “bad.”

If the body uses cholesterol everywhere, the presenter argues, it is unlikely to be a toxin in the simple sense.

Did you know? Many modern guidelines focus less on total cholesterol and more on overall cardiovascular risk and specific lipoprotein targets. You can see how major guideline groups frame these trade-offs in summaries like this update on European cholesterol guidance from the Family Heart FoundationTrusted Source.

The story the presenter tells about shifting “normal” numbers

This is where the video becomes a narrative about policy and perception, not just biology.

He describes a timeline where “normal” cholesterol thresholds dropped dramatically over a few decades.

Before the 1980s, he says, total cholesterol under 300 mg/dL was broadly considered normal, and clinicians did not react strongly until levels were well above that.

Then comes 1987.

In the video’s telling, the first statin was approved in 1987, and the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) launched its first major educational push the same year. He suggests this was not coincidence, and he frames it as an example of lobbying and marketing shaping healthcare.

Overnight, he says, “normal” shifted.

Total cholesterol targets moved down to the now familiar range, under 200 mg/dL desirable, 200 to 239 borderline high, and 240+ high.

Then the 1990s and early 2000s brought more focus on LDL.

He describes how later iterations emphasized LDL-C cutoffs, first making LDL under 130 mg/dL desirable, then lowering “optimal” to under 100 mg/dL, and then introducing even lower targets like under 70 mg/dL for people labeled high risk.

His frustration is not just that targets changed.

It is why they changed, and who benefited.

He cites a 2004 report in JAMA describing conflicts of interest, stating that 8 out of 9 panel members involved in one guideline iteration had financial ties to companies producing cholesterol-lowering medications. He argues that lowering thresholds effectively “creates” patients by redefining who qualifies for medication.

That is the video’s trade-off argument in a nutshell.

Lower thresholds might identify some people who benefit from earlier treatment, but they also expand medication use to millions whose real risk might be better explained by metabolic health.

What the research shows: Modern guideline discussions increasingly emphasize matching treatment intensity to overall risk and to specific lipid markers, rather than using a single total cholesterol cutoff for everyone. For one digestible overview of how European groups frame newer targets and risk categories, see the Family Heart Foundation summary of ESC and EAS guidanceTrusted Source.

Why “LDL is bad” is too simple: particle size and damage

LDL is not one thing in this video.

It is a category.

The presenter draws a sharp line between what he calls large, fluffy LDL and small, dense LDL. In his framing, LDL becomes dangerous mainly when it is damaged and shrinks into smaller particles.

He gives a specific size threshold: small dense LDL is less than 20.5 nanometers.

That number is part of his “precision” critique. Standard labs often report LDL-C in milligrams per deciliter, which is a mass measurement. But he argues that mass does not tell you particle size, and size changes the likelihood that LDL can penetrate the artery wall.

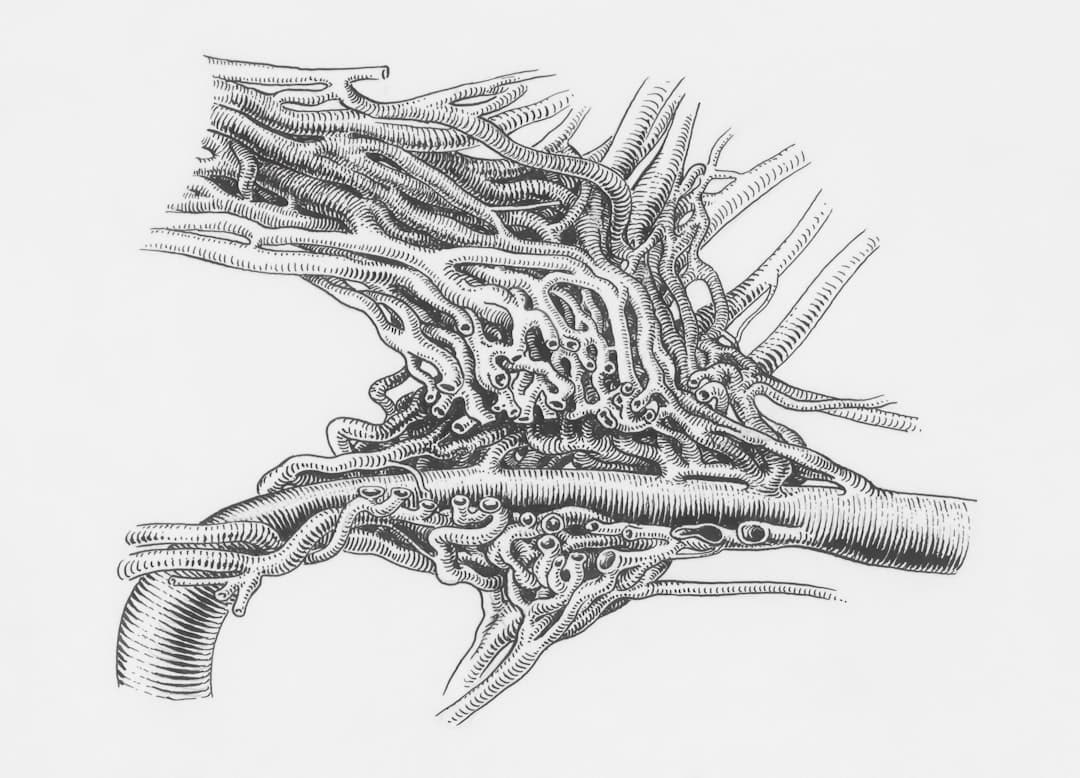

He also describes where plaque forms.

Not inside the blood vessel lumen, but within the artery wall. So the particles have to get into the wall first. Smaller particles, he argues, are more likely to slip through.

Then comes the immune response.

Damaged LDL, in his explanation, looks “foreign.” That attracts macrophages, immune cells designed to engulf debris and invaders. Macrophages consume the damaged LDL and become foam cells, which are a key component of plaque.

This is the video’s core mechanism story.

LDL is not automatically a villain. Damaged LDL in an inflamed, insulin-resistant environment is the problem.

Expert Q&A box

Q: If my LDL is high, does that automatically mean I am headed for a heart attack?

A: Not automatically. The video’s perspective is that LDL-C alone can miss important context, especially insulin resistance, inflammation, and whether LDL particles are small and dense. In real-world care, your clinician may consider your full risk profile, family history, blood pressure, diabetes status, smoking, and additional lipid markers.

Health Educator, MPH (medically cautious health writer)

The root-cause trio: insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress

The presenter returns to three drivers again and again.

Insulin resistance.

Low-grade chronic inflammation.

Oxidative stress.

He suggests these are the forces that convert “normal” LDL into “dangerous” LDL by oxidizing and glycating particles.

Glycation is his blood sugar link.

He describes how higher blood sugar can “stick” to proteins on LDL particles, damaging them. This is why, in his view, people can have “good” cholesterol numbers and still have heart attacks. If the metabolic environment is unhealthy, LDL can be damaged even when total cholesterol is not high.

He also makes a striking claim from the transcript: over 50 percent of heart attacks happen in people with total cholesterol under 200 mg/dL.

That claim is used to argue that total cholesterol is a weak standalone screening tool.

He then references population studies, including a Korean cohort observation (as he describes it) where men over 65 had the lowest death rate with total cholesterol around 250 to 270 mg/dL, and a Japanese study where cholesterol 220 to 260 mg/dL was associated with longer life than cholesterol under 200.

Those examples are meant to flip the emotional script.

If higher cholesterol can coexist with longevity in some groups, then cholesterol cannot be the whole story.

The trade-off is important, though.

Population observations do not mean “higher is always better” for every person. They do suggest that context matters, including age, illness, nutrition status, inflammation, and whether low cholesterol is sometimes a marker of other health problems. That is exactly why the video pushes for deeper metabolic testing.

Tests and ratios the video prioritizes (and why)

This section is practical, and it is one of the most actionable parts of the transcript.

The presenter argues that if you keep ordering only a standard lipid panel, you may keep getting the wrong story.

So he offers a different set of markers to discuss with your healthcare provider.

1) LDL particle testing (size and number)

He describes a more sophisticated test that counts LDL particles and evaluates particle size.

His emphasis is not just the total number, but the proportion of small particles.

In his view, a high percentage of small LDL is a red flag for insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

2) Ratios on a standard lipid panel

He acknowledges that even basic labs can be more informative if you interpret them differently.

He gives two ratios.

A. Total cholesterol to HDL ratio

He calls it useful, though not his favorite.

His point is that a low HDL often travels with inflammation and oxidative stress.

B. Triglycerides to HDL ratio

He says this is even better because triglycerides are a strong indicator of insulin resistance.

He shares common functional medicine cutoffs:

Then he adds his own clinical observation from years of checking labs.

On a low-carb pattern, he says triglycerides often run 50 to 80, and with HDL 50 to 70, the ratio is often around 1.

That is a very specific “video signature” claim. It reflects his bias toward low-carb eating as a way to improve insulin sensitivity and triglycerides.

Pro Tip: If you want to use ratios, ask your clinician to help you track them over time, not just once. A single snapshot can be misleading if you were recently sick, changing diet, or losing weight.

3) Inflammation and metabolic markers he wants added

This is where he draws a clear line between “standard ranges” and “optimal ranges.”

He argues that many labs only flag problems when they are already severe.

Here are the markers he highlights, with the specific targets he states:

This list is the video’s alternative roadmap.

Not “how low can you drive LDL,” but “how early can you detect metabolic dysfunction.”

»MORE: If you are building a lab checklist for a cardiometabolic visit, create a one-page tracker with dates and values for triglycerides, HDL, A1C, fasting insulin, and hs-CRP. Bring it to your appointment so you and your clinician can spot trends.

Statins in the video’s frame: trade-offs and blind spots

The presenter is not subtle about his concern.

He argues that statins can reduce mitochondrial energy production, and that this can “rob the cells of energy,” especially in high-energy organs like the brain, heart, liver, and kidneys.

That is his risk framing.

He also critiques the messaging that a pill “fixes” the problem. In his view, statins suppress a downstream marker while allowing upstream imbalances to continue.

Then he adds a mechanistic argument about why statins may not address the most dangerous LDL.

He says statins lower LDL in two main ways:

But he argues those receptors primarily clear “normal” large LDL, not the damaged small LDL that macrophages target. So LDL-C (the mass number) can drop while the proportion of small dense LDL stays the same or even rises.

This is a key trade-off message.

You may see a “better” LDL-C number and feel safer, while the metabolic conditions that damage LDL are still active.

At the same time, real-world cardiology uses statins because randomized trials show they can reduce cardiovascular events in many higher-risk groups. That is why this topic needs a clinician, not just a comment section. If you are at high risk, the decision is rarely “statin versus lifestyle.” It is often “lifestyle plus the right medication strategy for your risk.”

The video’s unique contribution is to challenge the idea that lower LDL-C automatically means the root cause is solved.

Expert Q&A box

Q: My doctor says my LDL is high, but my triglycerides are low and my HDL is good. What should I ask next?

A: The video would suggest asking about insulin resistance and inflammation markers, such as fasting insulin, A1C, and hs-CRP, plus whether particle testing (LDL-P and size) is appropriate for you. Your clinician can help interpret these in the context of your overall risk, including blood pressure, family history, and any prior cardiovascular events.

Health Educator, MPH (medically cautious health writer)

A “natural law” approach: lifestyle patterns tied to better markers

The presenter ends where he began.

Cholesterol is not the enemy.

The enemy is an “unnatural lifestyle” that drives insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

He lists examples that reflect his worldview of modern exposures and habits:

This is a broad list, and not every item has the same level of evidence. But the storytelling point is clear: he sees heart risk as an environment problem, not a cholesterol problem.

How to use this perspective without turning it into extremes

Here is a grounded way to translate the video’s approach into a conversation with your clinician, while staying medically neutral.

Start with metabolic health, not fear. Ask whether your current labs suggest insulin resistance, such as elevated triglycerides, low HDL, higher A1C, or elevated fasting insulin.

Pick a few markers to track consistently. The video emphasizes that standard “normal” ranges may miss early dysfunction. Consider tracking triglycerides, HDL, A1C, fasting insulin, and hs-CRP over time.

Match lifestyle changes to the marker you are trying to improve. If triglycerides are high, the video’s bias is that lowering refined carbs and added sugars may help. If hs-CRP is elevated, discuss sleep, stress, physical activity, oral health, and any chronic inflammatory conditions with your clinician.

Use medication decisions as risk management, not moral judgment. The presenter argues most people do better addressing root causes, and he says medication is not “never” appropriate. If you are high risk, your clinician may recommend medication while you work on lifestyle.

A single lab number should not be your identity.

It should be a clue.

Important: If you have chest pain, shortness of breath, stroke symptoms, or a history of heart attack, do not delay care while focusing on “root causes.” Seek urgent medical attention and follow your clinician’s treatment plan.

Key Takeaways

Sources & References

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is total cholesterol under 200 always the safest goal?

- Not necessarily. The video argues that many heart attacks occur in people with total cholesterol under 200, and that metabolic health markers may better explain risk for many people. Your safest target depends on your overall cardiovascular risk and should be discussed with your clinician.

- What is small dense LDL, and why does it matter?

- Small dense LDL refers to smaller LDL particles that the video describes as more likely to enter the artery wall and become part of plaque, especially when damaged by oxidation and glycation. Particle size is not shown on a basic LDL-C result, so some people discuss advanced lipid testing with their clinician.

- What labs does the video suggest besides a standard lipid panel?

- The presenter highlights triglycerides to HDL ratio, hs-CRP, fasting insulin, hemoglobin A1C, and homocysteine, plus LDL particle size and number if available. These can help you and your clinician assess insulin resistance and inflammation alongside cholesterol.

- Do statins fix the root causes of heart disease?

- The video’s viewpoint is that statins may lower LDL-C but do not directly reverse insulin resistance, inflammation, or oxidative stress that can damage LDL particles. Clinicians may still recommend statins for certain risk levels, so it is best handled as a shared decision based on your personal risk.

- What triglycerides to HDL ratio is considered favorable in the video?

- He mentions that many functional medicine practitioners consider under 2.0 lower risk and over 3.5 higher risk. He also notes that people who become insulin sensitive on a low-carb pattern often see ratios closer to 1, though individual results vary.

Get Evidence-Based Health Tips

Join readers getting weekly insights on health, nutrition, and wellness. No spam, ever.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.